Can Blockchain Stop Asia at the center of global manufacturing and cross-border commerce, which is a strength—and also a reason counterfeit trade can spread quickly. Counterfeit cosmetics slip into night markets and e-commerce listings, fake luxury goods move through unofficial distributors, and imitation pharmaceuticals and auto parts can endanger lives. The crisis isn’t just about lost brand revenue. It’s about consumer safety, trust in marketplaces, and the reputations of legitimate manufacturers who share the same routes, ports, and platforms.

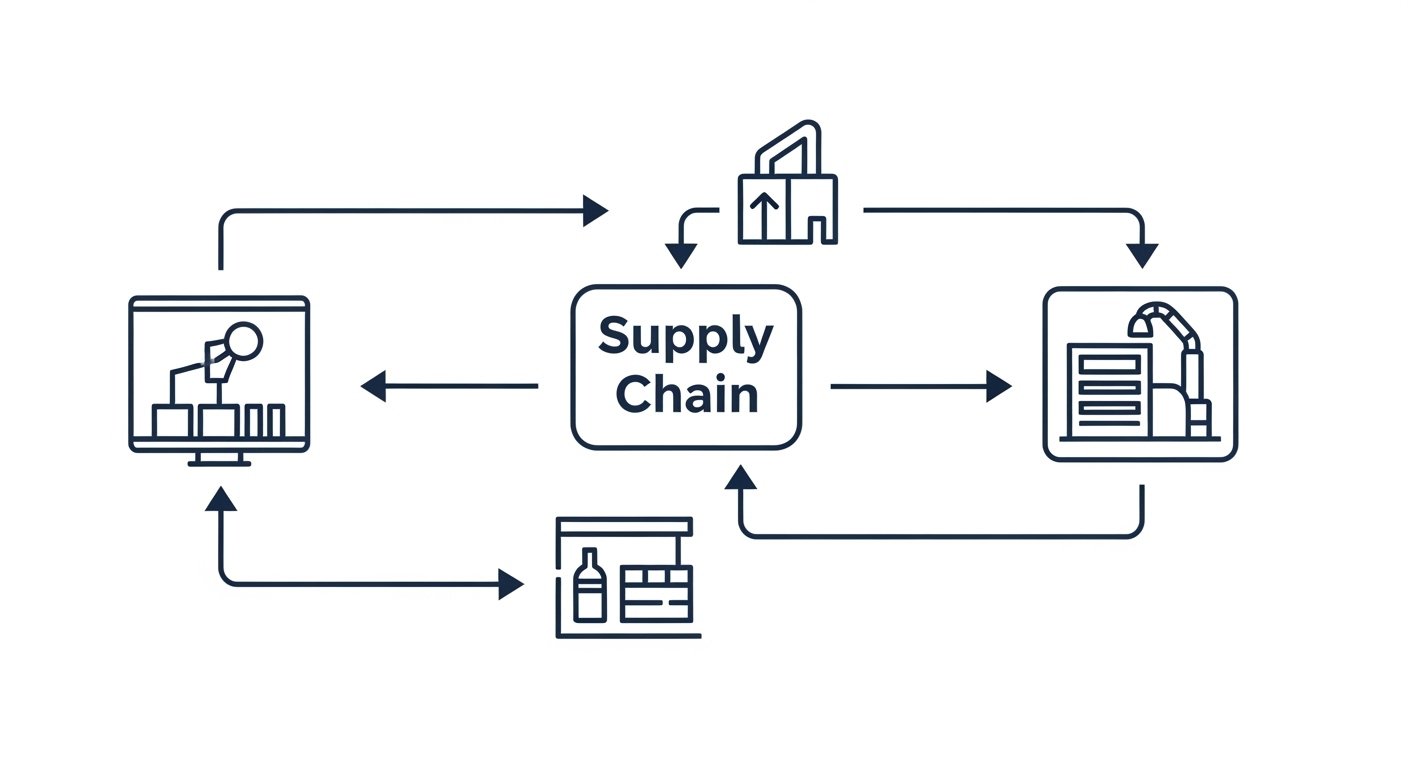

The deeper issue is that counterfeit networks exploit information gaps. Traditional supply chains rely on siloed databases, paper documents, and intermediaries who may not share data consistently. A product might change hands five or ten times before reaching a buyer, and each handoff is a chance to swap genuine goods for fakes. Even when brands use holograms, QR labels, or serial numbers, counterfeiters often copy them. Enforcement agencies also face a difficult puzzle: they can seize suspicious shipments, but proving origin and building a case requires records that are often incomplete or easy to manipulate.

That’s why blockchain keeps coming up in conversations about anti-counterfeiting. Blockchain is not magic, but it is built for something supply chains struggle with: creating a shared, tamper-resistant record across many parties who don’t fully trust one another. If Asia’s counterfeit goods crisis thrives on broken visibility, blockchain promises traceability, provenance, and auditable history—tools that could make counterfeiting harder, riskier, and less profitable.

Still, the real question isn’t whether blockchain can help. It’s whether blockchain can help enough—at scale, across borders, with messy real-world behavior—so that it meaningfully reduces counterfeits rather than becoming another pilot project that looks great in a slide deck. Let’s unpack where blockchain fits, what it can and can’t do, and what would need to change for blockchain to genuinely dent Asia’s counterfeit economy.

The anatomy of counterfeit supply chains in Asia

Counterfeiting in Asia isn’t a single system. It’s a web of small workshops, gray-market distributors, corrupt actors, online sellers, and logistics routes that constantly adapt. A counterfeit product may be assembled from legitimate components. It may be “overproduced” in a real factory beyond the authorized amount. Or it may be diverted from one region to another and relabeled, becoming “counterfeit” from a legal standpoint even if the item is physically real.

What makes the crisis persistent is that today’s verification tools are fragmented. Brands may have internal tracking, customs may have inspection data, e-commerce platforms may have seller histories, and logistics providers may have shipping scans. But these datasets rarely connect in a way that creates end-to-end visibility. When data does connect, it is often centralized and therefore vulnerable: a single database can be altered, hacked, or selectively shared.

This is where blockchain enters the discussion. A well-designed blockchain system can align multiple parties around one shared ledger, creating a practical baseline for supply chain transparency. In theory, every handoff becomes a verified event. In practice, the devil is in how those events get recorded and whether participants have incentives to be honest.

What blockchain actually does well for product authenticity

It’s easy to oversimplify blockchain as “a database,” but its value is more specific. Blockchain is a distributed ledger: instead of one organization controlling the records, multiple participants validate them under agreed rules. Once records are written, altering them is difficult without detection. That immutability is useful in disputes, audits, and investigations—especially when counterfeiting relies on plausible deniability.

For counterfeit prevention, blockchain is strongest at three jobs: establishing provenance, improving traceability, and enabling shared verification without a single gatekeeper. If a product’s lifecycle events—from manufacturing to shipping to retail—are recorded and validated, buyers and regulators can check whether a claimed origin matches the ledger history. A counterfeit item may still exist, but it becomes easier to flag inconsistencies and isolate where the substitution likely occurred.

However, blockchain doesn’t automatically prove the physical product is genuine. It proves that the ledger entry says it is. That distinction matters, because counterfeiters often attack the “bridge” between physical items and digital records. Solving the bridge problem is where the most practical anti-counterfeit designs focus.

The “physical-to-digital” bridge: where most systems fail

A blockchain record is only as trustworthy as the input. If someone can attach a legitimate QR code to a fake handbag, the ledger may show a “real” item even when the buyer holds a counterfeit. So the critical challenge is binding the physical product to a digital identity in a way that is hard to clone, reuse, or transfer.

Secure identifiers and tamper-evident packaging

To strengthen the bridge, brands combine blockchain with tamper-evident packaging, serialized tags, and security features that are difficult to reproduce. For example, a tag can be destroyed when removed, preventing reuse. Some systems link the tag to a one-time activation step so that an already-activated identity is treated as suspicious. The goal isn’t perfection—it’s raising the cost of counterfeiting and increasing the odds of detection.

IoT, RFID, and sensor-backed chain-of-custody

When blockchain is paired with RFID scans, GPS events, temperature sensors (for pharmaceuticals), and logistics checkpoints, it becomes harder for counterfeit goods to slip in unnoticed. If a cold-chain medicine shows a temperature breach or missing scans along a route, investigators can focus on that gap. In these setups, blockchain acts like a shared timeline for events rather than a standalone authenticity stamp.

Consumer authentication that’s harder to spoof

A common approach is letting buyers scan a code and verify product history. But consumer-facing verification only works if the experience is simple and the system prevents easy copy attacks. Some blockchain designs address this by using rotating codes, challenge-response verification, or app-based cryptographic checks. Done well, blockchain makes it feasible for millions of consumers to participate in product authentication without needing to trust one company’s database.

Smart contracts and automated enforcement in anti-counterfeiting

A major advantage of blockchain is that it can support smart contracts—rules that execute automatically when conditions are met. In anti-counterfeiting efforts, smart contracts can enforce trading and distribution constraints. For example, a distributor might only be able to transfer ownership of an item on the blockchain if it came from an authorized upstream party. If a seller tries to list inventory that has no valid ledger history, marketplaces can flag it automatically.

This is where blockchain becomes more than traceability; it becomes a compliance layer. In Asia’s complex trade environment—where goods pass through free trade zones, parallel import channels, and multi-tier distribution—automated rules can reduce the “gray areas” that counterfeit networks exploit. But for smart contracts to matter, retailers, logistics providers, and platforms must actually use the same rails.

Why Asia is a unique test for blockchain traceability

Asia’s markets are diverse. You have high-compliance environments with strong digital infrastructure, and you also have fragmented informal commerce where paper receipts and cash still dominate. Blockchain solutions must work across this spectrum.

In cross-border trade, Asia also faces jurisdictional complexity. A product might be manufactured in one country, packaged in another, sold online from a third, and delivered to a fourth. Each border introduces different data standards, customs procedures, and legal interpretations of authenticity. The promise of blockchain is that it can provide a consistent record even when institutions vary. The risk is that without shared standards and incentives, the ledger becomes yet another silo—just a more complicated one.

Real-world use cases where blockchain can move the needle

The most convincing blockchain anti-counterfeit stories tend to come from categories where provenance really matters and where scanning checkpoints is realistic.

Pharmaceuticals and medical supplies

Counterfeit medicines are among the most dangerous products in Asia’s counterfeit economy. Here, blockchain-based traceability can tie batch numbers, manufacturing certificates, shipping conditions, and pharmacy dispensing events into one verifiable chain. When combined with regulatory serialization, blockchain can help detect diversion, tampering, and unauthorized resellers.

Luxury goods and collectibles

Luxury brands care about brand trust and resale value. Blockchain can support digital product passports that follow an item into the secondary market. When the same identity is required for servicing, repair, or resale authentication, counterfeiters face a tougher environment. Some brands use NFTs or tokenized certificates as part of this approach, but the core value is still blockchain-anchored provenance—proof of ownership history and verified origin.

Food, agriculture, and premium exports

Food fraud and mislabeled origin claims are a large issue in Asia. Blockchain systems can record farm-level data, processing steps, and shipping events to support authenticity claims like “single-origin,” “organic,” or “sustainably sourced.” The goal is to protect both consumers and honest producers. In these sectors, blockchain works best when there are structured checkpoints already in place.

The adoption challenge: incentives, cost, and coordination

If blockchain were simply a better database, it would already be everywhere. The hardest part is coordination. For blockchain to reduce counterfeits, enough participants must record events honestly and consistently. That requires incentives.

Manufacturers may adopt blockchain to protect brand value, but small suppliers might see it as extra work. Logistics companies might participate if it reduces disputes and improves efficiency. Retailers and marketplaces might integrate blockchain if it lowers counterfeit risk and boosts buyer trust. Governments might support blockchain if it improves tax compliance and consumer safety. But aligning all these motivations is nontrivial.

Cost is another barrier. Secure tags, scanning infrastructure, integration with existing ERP systems, and training across a multi-tier supply chain can be expensive. For lower-margin products—where counterfeiters thrive because buyers are price-sensitive—adding per-unit costs is a serious hurdle. This is why blockchain anti-counterfeit programs often start in high-value categories and gradually expand.

Privacy, competition, and the fear of sharing data

A common misconception is that blockchain requires full transparency. In reality, many enterprise blockchain systems use permissioned access and privacy-preserving techniques so participants only see what they need. Still, companies worry that sharing supply chain data could reveal pricing, supplier relationships, and volumes—strategic information in competitive Asian markets.

To succeed, blockchain designs must balance supply chain transparency with confidentiality. That often means storing sensitive data off-chain while anchoring proofs on blockchain, or using cryptographic methods to prove compliance without revealing raw details. These design choices determine whether a blockchain network feels like a shared utility or like a surveillance system—an important difference for adoption.

Can blockchain work with e-commerce platforms and social commerce?

A huge portion of Asia’s counterfeit crisis now flows through online channels: marketplaces, social commerce, messaging apps, and livestream selling. Here, blockchain can help, but only if platforms integrate verification into listing and fulfillment.

One practical model is requiring sellers of certain categories to prove inventory provenance via blockchain records. If an item can’t show a valid chain-of-custody, the platform can limit visibility, require additional verification, or block the listing. Another model ties blockchain identities to fulfillment centers so scans occur during warehousing and shipping. This makes “switching” inventory harder.

But online counterfeiting is highly adaptive. Sellers rotate accounts, move between platforms, and exploit cross-border loopholes. Blockchain can raise friction, yet platforms must still invest in enforcement, identity verification, and dispute resolution. In other words, blockchain can strengthen the backbone, but the muscles still need to move.

The uncomfortable truth: blockchain won’t “solve” counterfeiting alone

Even a perfect blockchain ledger can’t stop a determined counterfeiter from manufacturing fakes. What it can do is reduce the profitability and scalability of counterfeiting by shrinking the places where fakes can pass as real. It can also speed up investigations by making it easier to pinpoint when and where a substitution occurred.

The biggest risks to blockchain success are predictable: garbage data in, weak physical tagging, low participation, and fragmented standards. If only one brand runs its own blockchain program, counterfeiters can route around it. If every brand uses a different approach, suppliers face integration overload. If governments don’t recognize blockchain records in enforcement workflows, the ledger won’t translate into action.

So the realistic goal is not a world where counterfeits disappear. The realistic goal is measurable improvement: fewer counterfeit listings, fewer dangerous fakes in critical categories, faster recalls, stronger consumer trust, and better accountability across the trade network.

What it will take for blockchain to meaningfully reduce Asia’s counterfeit trade

For blockchain to become a genuine force against counterfeits in Asia, three shifts matter most.

First, digital product identity needs to become standard. Whether the mechanism is a secure tag, a digital product passport, or another method, products must carry a durable identity that can be verified without specialized equipment.

Second, interoperability needs to improve. Blockchain networks must connect across brands, logistics providers, and borders, or at least use common standards so data can be trusted and compared. Without this, blockchain becomes isolated islands.

Third, incentives must align. Suppliers need benefits for participation, platforms need operational wins from verification, and regulators need usable signals from the ledger. When blockchain is tied to reduced chargebacks, easier customs clearance, better financing terms, or higher marketplace trust scores, adoption becomes rational rather than aspirational.

Conclusion

Blockchain can’t single-handedly “solve” Asia’s counterfeit goods crisis, because counterfeiting is driven by economics, enforcement gaps, and consumer behavior—not just missing data. But blockchain can absolutely change the game where counterfeits depend on anonymity and supply chain confusion. By enabling stronger traceability, clearer provenance, and shared verification across parties, blockchain can make it harder for counterfeit goods to blend into legitimate commerce.

The most likely future is not a sudden breakthrough, but steady integration: blockchain-enabled product identities in high-risk categories, wider adoption through logistics and marketplaces, and gradual standardization across the region. If Asia’s stakeholders treat blockchain as infrastructure—combined with secure physical tagging, platform enforcement, and regulatory action—it can meaningfully reduce counterfeits, protect consumers, and restore trust. The crisis is massive, but blockchain gives Asia a tool it has long lacked: a credible, shared record that counterfeiters can’t easily rewrite.

FAQs

Q: Is blockchain the same as using QR codes to verify products?

Not exactly. A QR code is just a label, and it can be copied. Blockchain is the system that records and validates a product’s history and ownership events. QR codes can be one interface to that history, but blockchain adds the tamper-resistant ledger and shared verification that a simple code alone cannot provide.

Q: Can blockchain stop counterfeiters from making fake goods?

No. Blockchain can’t physically prevent counterfeit manufacturing. What blockchain can do is make it much harder for fake goods to pass as authentic inside legitimate supply chains and online platforms by improving product authentication, traceability, and accountability.

Q: What industries in Asia benefit most from blockchain anti-counterfeiting?

Industries with high safety risk or strong brand premiums benefit most, such as pharmaceuticals, medical supplies, luxury goods, premium foods, and regulated components like auto parts. In these categories, blockchain-based provenance and chain-of-custody can deliver clear value.

Q: Does blockchain require public transparency of company data?

Not necessarily. Many enterprise blockchain systems are permissioned, meaning access is controlled. Sensitive data can be kept private while still using blockchain to anchor proofs and maintain an auditable trail for compliance and dispute resolution.

Q: What’s the biggest reason blockchain anti-counterfeit projects fail?

The biggest reason is weak adoption and weak “physical-to-digital” binding. If participants don’t record events consistently, or if product identities can be copied onto fakes, blockchain won’t help much. Successful systems combine secure identifiers, real scanning checkpoints, and incentives that make honest participation worthwhile.